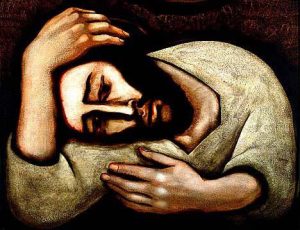

Sometimes that silence can build into an overwhelming obstacle, a palpable barrier that holds life back. There might be some small talk, some chatter about the details of living. But to engage in true dialogue seems too risky. For to address the other directly would release a torrent of complaints and hot emotions which would throw life into turmoil and, more importantly, reopen hearts to be hurt again. So people end up trapped, walled into a voiceless void, unable to summon the courage to break the silence.

The escape from such a prison occurs when we choose to push through the barrier and address the other. Simple words such as, “We need to talk,” or, “This has to stop,” are an act of faith, a willingness to throw ourselves back again into the hurt and misunderstanding without knowing what will result. Often such words emerge from our desperation, from the knowledge that the risk of communication, however uncertain, has become less painful than the silence which is killing us.

Psalms push through the barrier of silence. Most of the psalms are not descriptions of God, or accounts about God, but cries to God. When a psalm is prayed sincerely it breaks the silence and takes the risk of opening communication. The most important word in the psalm is the word which addresses God. Grammatically this word is in the second person or vocative voice. Words such as “Lord” or “my God” anchor the psalm, situating it within a relationship. Often the address is a complaint, because the psalmist is in need and God seems to be absent.

The most prevalent type of psalm is the one we have called the individual prayer of petition. Here the psalmist is beset by trouble, usually sickness, false accusation, or armed conflict. These evils are not viewed from some abstract angle. They are immediately related to a personal relationship. God is addressed as someone who is involved, capable, and responsive to human pleading.

God is invoked in thoroughly human terms, as if God were a negligent spouse or friend. Once the silence is broken, emotions, accusations, and arguments spill forth. The personal hurt and disappointment of the one who prays is obvious: “Why, O Lord, do you stand far off?” (Ps 10:1); “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?” (Ps 13:1); “Save me, O God, for the waters have come up to my neck” (Ps 69:1); “O God, do not keep silence; do not hold your peace or be still, O God” (83:1); “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps 22:1).

The directness and honesty of these invocations reveal the nature not only of the psalms but also of all genuine Christian prayer. Lengthy meditations could be drawn from their power. Here, I will offer only three points for reflection.

1) We must pray as the people we are.

Because prayer activates our most profound relationship, there can be no phoniness when we speak to God. We may wish to put our best foot forward, to make a good impression; but it is more important to be real than to be polite. We must stand as our real selves before God with all our warts and imperfections. The only person God can love is the person who actually exists. That is why it is better to pray as a genuine sinner than as a fake saint.

Therefore, human emotions are not only acceptable but necessary in prayer. If we are angry, honest prayer will show that anger. If we are afraid, genuine prayer will not attempt to dissemble courage. If we are disappointed with God’s care for us, real prayer will let that disappointment show. Of course, prayer has the power to transform us. But that process can only take place if we begin with what is real, with the person who we really are. It is then that God can touch us and reshape us.

2) Honesty indicates intimacy.

The strong feelings and recriminations which fill the psalms may seem out of order when one addresses the creator of the universe. But their extensive presence within the psalms is not an indication of disrespect but rather of intimacy. It is only when we are close to God and cherish that intimacy that we will pray what we really feel. We are polite to strangers; we are brutally honest with those on whom our survival depends. When we have been hurt in a close relationship or disappointed in another’s behavior towards us, it may take courage to speak. But when we do address the person whom we love, it is not courteous chatter which emerges but utter honesty: “You have let me down; why did you do that?”

The opposite of love is not hate. It is indifference. We do not waste our energy on people who are unimportant to us. Strong emotions, even negative ones, indicate that we care enough to feel. Only a deep relationship can risk such raw passion. Only intimacy will accept such truth.

3) God adjusts to our limitations.

There is no parity in our relationship with God. God is creator; we are creatures. God is pure spirit; we are flesh and blood. God is without limitations; we are bounded by sickness, failures, and death. According to the great theologians of our tradition, God is totally other. God knows all things, even the future. From this theological tradition there is no need for prayer, no need for us to ask God for anything. God knows what we need before we ask it and has already decided to save us in a way that is frequently beyond our imagining. Our prayers can affect no change in God, because God is perfect, beyond our power to persuade or influence. This is the God of the theologians.

How different is the God of the psalms! This God is constantly invoked, cajoled, and even questioned by the psalmist. God is addressed as one who will respond as humans do. In most psalms of petition the psalmist is quick to inform God of the exact need which must be addressed. The psalmist does not shrink from bargaining with God or appealing to God’s pride. Unlike the God of the theologians, the God of the psalms is addressed in the same way we would address any human from whom we sought a favor.

It is impossible to completely reconcile the God of the theologians and the God of the psalms. But I would suggest that what we find in these inspired songs of Israel is a God who is willing to accommodate the divine nature to the human condition. In the psalms the One who is totally Other is willing to be addressed in a manner which we can understand. God assumes the qualities of a human partner. This move is not only humbling but necessary. For unless God chooses to become like us, any attempt we might make towards prayer or relationship would prove fruitless. In this way the God of the psalms foreshadows the incarnation, that definitive act of love by which God assumed a human nature in Jesus. In our dealing with God, the need is always the same: we can never relate to God on God’s level, so God must always choose to relate to us on ours.

Given this act of accommodation on God’s part, we should not hold back from using it. When we are in need and God seems absent, when evil attacks and God does not save us, we should not bite our lip and hold in our frustration. We should take the risk and speak to God with all the honest emotion that would characterize an intimate human relationship. We should break the silence and pray.

Fr. George’s reflection is helpful to us because it draws a stark parallel between the challenges we have in human relationships and the fact that those challenges crop up in our relationships with God, too. Is it easier to work on honesty and those things which cause indifference with those whom we can see and with whom we must interact daily or is it easier to be honest with God, whom we do not see? Do we trick ourselves that we are honest with God, not indifferent to Him because we cannot see the hurt on His face or the pain we are causing as we can with humans? How do we see clearly what our dishonesty does to our relationship to God if we cannot see His face and what that face conveys to us about our failures in that relationship? I guess I will choose to simply practice this behavior of honesty with those God has placed in my life so that I will have some muscle memory when it comes to trying to be more honest with God.

Jeff,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment on this article. The question of honesty with God is a profound one. But I fully agree that our best guide is honesty with others. Honesty in one relationship cannot help but influence another.

Thank You , Fr George ! This web site is both thought provoking and powerful. Just what I was looking for to help me through these ” Golden Years . ” ….and in the comfort of my home.

Mary Ann

It is so comforting to remember that my own inadequacies in prayer do not disappoint God; that God already knows my every need. But if the opposite of Love is “indifference”, am I being sinful when I avoid people with whom I have conflict? Honesty is not always appreciated even when delivered gracefully. I think you are saying that after the silence has been broken, and honesty has been risked, it is OK to avoid future conflict. MK

Thanks Micky. Avoiding people is not indifference. It is a strategy which may be necessary in some circumstances. It is possible to care for some people but make the decision that interaction or complete honesty with them would not be beneficial.

I love that verse! I believe it’s often over-looked. It has alawys compelled my heart to look deeper & further into God’s word, and to my understanding of it. It’s been a summons to wisdom & to becoming a workman approved. It is a rallying cry to becoming “reason-able”. It is also a reminder to stand still often and survey the hope that has been birthed & grown throughout my life. I appreciate the many dots you’ve connected to hope here.

Amazing things can happen in silence. It is in this space that the real you shines through. You gain clarity. The answers that have eluded you become clear as day. You make the amazing realization that you are not your thoughts and feelings, that you are pure consciousness and these are entities that are constantly passing by in various forms.