Matthew and City Life

Christianity was an urban phenomenon. Although the origins of the Christian movement in the ministry of Jesus were rooted in the rural soil of Galilee, the spread of the gospel took place in the urban centers of the ancient world. Because the Roman empire made easy travel possible, the early apostles gravitated quickly to the great cities of Antioch, Alexandria, Byzantium, and Rome. In those cities one would find people from all parts of the empire. A flourishing commercial climate allowed both goods and ideas to be exchanged. People were meeting and influencing each other on an unprecedented scale.

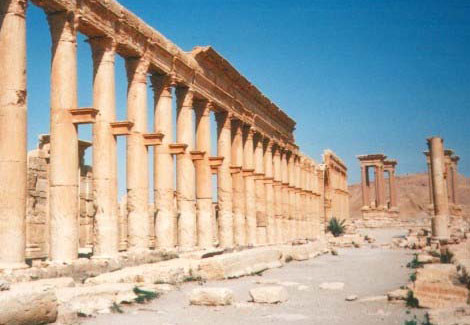

The city of Antioch in Syria is often suggested as the place where the Gospel of Matthew was written. Even though the suggestion cannot be proven, it is likely that Matthew was composed in a city much like Antioch. For there are aspects of the gospel which indicate an urban setting.

In describing the locations for his narrative, Matthew mentions a “city” twenty-six times. Mark, who Matthew uses as a source, only mentions a “city’ eight times. Matthew also seems to reflect the wealth of a great urban center. Both Luke and Matthew tell the parable of the servants who received from their master different amounts of money to invest (Matt 25:14-30; Luke 19:11-27). Yet in Matthew’s version the amounts that are entrusted to the servants are fifty times greater than the amounts in Luke. Throughout his gospel, Matthew mentions gold and silver more frequently than Mark and Luke together.

Wealth, however, is not the primary indication of Matthew’s urban setting. Even more convincing is the striking mix of ideas which we find in this gospel. For there is an obvious tension in Matthew’s narrative which is best explained if we see it flowing from the pluralistic setting of city life.

The Tension of Matthew’s Gospel

Matthew is not a homogenous gospel. It contains clear and definite statements which pull in opposite directions. Some statements seem to close the gospel off from those who are not Jewish (Gentiles). Other statements welcome Gentiles with open arms.

Several directives in Matthew’s gospel describe Jesus’ disciples as those who are to be different from the Gentiles. In Matt 5:47 the disciples of Jesus are told that if they only greeted members of their community, they would be doing no more than what the “Gentiles do.” In Matt 6:7 they are warned not to pray “as the Gentiles.” In Matt 6:32 they are told to be different from Gentiles who worry about material things. In Matt 20:25 they are told that they must not exercise authority as is the custom of Gentiles. In two places Matthew indicates that missionary efforts should not be addressed to Gentiles. When Jesus refuses to heal the Syrophoenician woman’s daughter, he tells her, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 15:24). When Jesus sends out the disciples to preach, he tells them, “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:5-6).

Yet another group of statements in the gospel seems to include Gentiles within the community and its mission. In Matt 4:15-16 a quotation from Isaiah is used to describe Jesus’ mission as a light dawning upon the Gentiles. In Matt 12:18-21 another Isaiah passage associates Jesus as the Servant of Yahweh who will “proclaim justice to the Gentiles” and “in his name the Gentiles will hope.” The Magi of the infancy narrative portray Gentiles coming to worship Christ (Matt 2:1-12). The great commission which concludes the gospel announces that the good news is to be taught “to all the nations” (Matt 28:18-20).

How can we explain this tension within Matthew’s gospel? One plausible suggestion is that the gospel contains statements from different periods in the life of Matthew’s community. Jesus and all the early apostles were Jewish. The early Christian movement saw itself as a part of Judaism. In the early years after the resurrection, to be a disciple of Jesus entailed being Jewish as well. As Matthew’s community began its life, it was probably very tied to its Jewish roots, distinguishing itself from Gentiles and believing that its mission should be only to Jews. As time passed, however, things began to change. Gentiles were eager to follow Christ and Matthew’s community gradually opened itself to welcome them. The possibility that Matthew’s community was located in a great urban center such as Antioch would certainly facilitate this development. As Jews and Gentiles interacted in the economic, cultural, and civic dimensions of city life, the gospel of Christ could easily spread from Jews and take hold in Gentile hearts.

The Gospel of Matthew has preserved perspectives from different stages of its community’s history. The statements which limit the gospel mission only to Jews derive from its early years. Those which recognize a mission to all nations express the later stages of its history. Moreover, the decision to retain diverse attitudes from different periods is not only of literary significance. It also reveals a profound pastoral approach.

Matthew’s Pastoral Approach

Although Christianity began as a movement within Judaism, by the end of the first century it was standing as a religion in its own right, composed primarily of Gentiles. The mission to the Jews had largely failed. Gentiles had responded to the gospel in great numbers. In the late first century, a community such as Matthew’s would find itself composed of a small traditionalist core of Jews significantly outnumbered by an ever-growing contingent of Gentiles. In such a context it would have been easy for the conservative minority to dig in its heels and attempt to cut off further growth. It would also be understandable for the new majority of Gentiles to impose its will and silence the Jewish voice.

The pastoral approach of Matthew’s gospel attempts to discourage both of these one-sided strategies. The gospel opts for an inclusive approach, seeking to bridge the gap between a Jewish past and a Gentile future. It does not discard the traditions of the original Jewish perspective, but absorbs them into a new synthesis. By giving prominence to the moral teaching of the Torah and frequently inserting quotations from the Hebrew scriptures, the gospel assures the traditionalist minority that they have a place in a church becoming ever more Gentile.

Matthew might be describing himself when he provides a saying of Jesus found only in this gospel: “Every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old” (Matt 13:52). The new is brought out first, but the old is not thrown away.

The greatest gift of Matthew’s gospel to our church today may be its pastoral approach. Matthew holds together all the parts of the tradition so that all members of the community might recognize themselves in its narrative. Matthew’s vision is inclusive. It warns us about throwing out too easily that which is old. It teaches us to honor the minority voices and ideas which are no longer in vogue. Even as it orientates itself for the future, it still treasures what is valuable from the past.

In Matt 9:17 Jesus warns his disciples that if they pour new wine into old wineskins, the skins will burst and both the wine and the skins will be destroyed. That is why new wine should only be poured into new skins. At the end of this small parable Matthew adds that by doing this “both are preserved.” That comment summarizes Matthew’s pastoral attitude. The gospel strives to preserve both the new wine and the old wineskins. Such an orientation is not only a good way to write a gospel. It is a healthy and positive way for any community to live.